Renowned Nev. epidemiologist talks diseases

By Susan Wood

RENO – And the doctor worked on.

Questioning whether Mary Guinan has fulfilled a storied career in medicine is like asking Nevadans if they want clean air and Americans if they want to be disease free.

A notable epidemiologist, the 76-year-old distinguished physician not only served as the Silver State’s chief health officer from 1998 to 2002 and 2005-06, she was on the front lines of the first AIDS cases while working for the Centers for Disease Control for 20 years.

And now, an East Shore resident, she has written a book – “Adventures of a Female Medical Detective.”

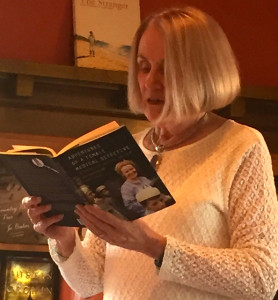

She read excerpts and signed copies this week at Sundance Books in Reno.

Mary Guinan, left, talks with people after the June 7 reading at Sundance Books in Reno. Photos/Susan Wood

Much of the book chronicles those critical, painful years of treating the AIDS epidemic, with all its stigmas and challenges. It was a shameful, fear-based era in American health. AIDS represented a death sentence to mostly gay men, who were disowned and disenfranchised from society.

The disease, which burst on the scene in mainly metropolitan areas in the early 1980s, has claimed 36 million. Still today 50,000 cases are reported each year. In the early years, the team with Guinan at the CDC launched an undaunted fight to understand AIDS, which has no cure or vaccine – just treatment for the HIV immune system deficiency symptoms. These medical soldiers’ work was documented in Randy Shilts’ book “And the Band Played On.” There’s a scene in the story in which Guinan and her colleague realize they both connected with Patient 0, the first to be chronicled. Their “aha” looks told the story of the monumental task ahead of them as they tried feverishly to understand and isolate the disease.

But it was the reaction of society to those infected that left Guinan with the sinking feeling that discrimination was alive and well in the United States.

“The fear was overwhelming. People were thrown out of their apartments, lost their jobs,” she told the group. She told Lake Tahoe News earlier that some mothers approach her after her talks declaring they disowned their gay sons with AIDS, “a decision they’ve regretted the rest of their lives.”

Any regrets from the front line of the AIDS fight?

“I wished we could have eliminated the hatred,” Guinan said in the LTN interview, while adding: “My son (at 30) didn’t know much about the time. He read the book and couldn’t believe what life was like. People of his generation couldn’t care less who’s gay.”

She even conducted a talk in Ireland and thanked the citizens for passing an initiative to legalize same-sex marriage.

“I told them they shamed New York City,” Guinan said.

The chapter of her book dictating how homophobia gripped the nation in the 1980s and’ 90s was difficult to write, she told the group.

“It took me a long time to write it because it was so sad,” she said, while a hush came over the room. “Still people don’t want to be tested because they don’t want to be identified.”

Mary Guinan

She read a passage about the story of a woman shamed by her husband, a preacher, who gave her AIDS.

Guinan also talked about working as the top medical officer for Nevada at a time when Fallon harbored the largest cluster of leukemia ever recorded. Normal for the health department is one case every five years.

“We had 15 cases in a 2½-year period there,” she said. The audience gasped.

She had indicated to LTN one of her most crowning achievements for Nevada centered on the Clean Indoor Air Act of 2005. The tobacco and casino industries fought hard against it, spending millions of dollars on a campaign against it.

“Nevada has the highest rate of childhood asthma,” she said.

After the reading on June 7, those who came out assessed the event as a success. It hit more close to home for some than others.

“She’s a fascinating woman with a fascinating life. What she said about how no one knows public health is so true,” Pam Young said after the talk. Young, who retired from the Washoe County Public Health Department, came out in support of Guinan’s work with colleague Ellen Marston.

“Her career is amazing,” one woman whispered after Guinan wrapped up her talk at Sundance books.

Glass ceiling?

Guinan’s journey to public health was varied and unscripted. She shared with the audience stories of how she tried to break down gender barriers by opting for professions not commonly held by women.

First, it was President John F. Kennedy’s insistence on reaching the moon that made her dream of being an astronaut some day.

She graduated from college a chemistry major, but few jobs were open to women. “Help wanted” ads back then were divided by men and women. For her college background, she landed in Queens in a gum factory. She was asked to develop a “kissing gum,” so her bright idea was to dye the surface sugar pink. The creation turned into a debacle as an explosion of pink sprayed so hard, it turned one of her male colleague’s underwear pink.

When JFK was killed, she pondered his famous speech: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what can I do for my country.” With that, she got a job in the medical branch of the University of Texas in Galveston, where astronauts gathered often and talked about their exotic experiences in space. The fire was lit. She took an aviation course, but ultimately the quest didn’t work out. She instead enrolled in a post-doctoral fellowship, consequently attended medical school, and the rest is history.

Of Irish descent, she always remembers her parents dictating that “you could do whatever you want to do” in America.

Still marveling this day at 165 countries in the world fighting to eliminate small pox, the ambitious New Yorker looked broader than the U.S. for her next quest.

So when the World Health Organization’s infectious disease division provided an assignment to eradicate the dreaded disease, she jumped all over the job and onto a plane to India. The assignment that called for quarantining the infected while getting supplies over swollen rivers turned out to be challenging until one day, a man in a big black car said he wanted to help by giving her an elephant to ride over the rivers.

“I wasn’t sure what to say,” Guinan told the bookstore attendees, who were snickering at the notion.

“I wasn’t sure what to say,” Guinan told the bookstore attendees, who were snickering at the notion.

It worked out, and she kept the elephant for three weeks. Needless to say, her expense reports got a second look when she claimed an elephant driver.

She left India in 1975, and within a year, small pox was no longer a threat.

“It was intoxicating for me to be a part of such as program,” she said.

From that point forward, she was hooked on fighting infectious diseases.

She even became known as “Dr. Herpes” when the syndrome was hitting all the news cycles. She served on a panel discussion in Utah on cold sores, and Dan Rather came on the CBS News and gave her the label.

The transition to AIDS was almost seamless. Her detective work was put to the test.

Three years before she left the CDC in 1998, a cocktail of drugs was developed to treat the symptoms.

“It was like a miracle happened,” Guinan told the group.

But the fight over diseases never ends.

The founding dean of UNLV’s school of Community Health Sciences, her most recent concerns go far beyond small towns and the state – and even her country.

“People need to be reminded of how bad it was during the AIDS epidemic and make that association with the Zika virus,” she told Lake Tahoe News.

And at her book reading, a few people asked her about the latest disease caused by mosquito bites. Her main concern lies with it being transmitted sexually. Therein lies a perfect storm of events – the virus is rampaging in countries with mass populations and few options of birth control.

The Summer Olympic Games’ host city Rio de Janiero is in one of the countries.

“It’s a big problem,” Guinan answered one inquiry from the book reading. “(Olympic officials are) telling people to wear long sleeves and wear bug repellent. How effective that’s going to be remains to be seen.

“We have to do our jobs to try to find out people who have visited (these countries) and so they can be tested,” she said. The Zika virus, which is especially potent at causing birth defects, can be harbored for a decade in a carrier.

“It reminds of the AIDS virus,” Guinan said of that parallel.

The epidemiologist also fielded a question about the highly controversial issue of some parents refusing to vaccinate their children. Her response to the article in a medical science journal supporting that stance: “The damage is done.”