Tree mortality at ‘epidemic’ level in Tahoe basin

By Kathryn Reed

STATELINE – A healthy forest is the best deterrent to stop the bark beetle infestation. The problem is Tahoe forests aren’t healthy.

“We have seen this march of dead trees grow through the summer,” Joanne Marchetta, Tahoe Regional Planning Agency executive director, told her board this week.

Orange is becoming a dominant color in pockets of Tahoe, with the North Shore being hit the hardest. Sugar pines are dying off in alarming numbers.

With this being the fifth year of drought and forests being overly dense, the beetles are winning. Trees are too weak to fight off these native species. The dead trees then create more fuel for a wildfire.

The bi-state regulatory agency has been working with the Tahoe Fire Fuels team to devise a plan to combat the spread.

On Aug. 24 the Governing Board heard a presentation by fire and forest experts about the infestation. The Lake Tahoe Basin Tree Mortality Task Force has been created to spearhead the effort. There will be a larger discussion on Aug. 30 between local and state officials in advance of the following day’s Environmental Summit.

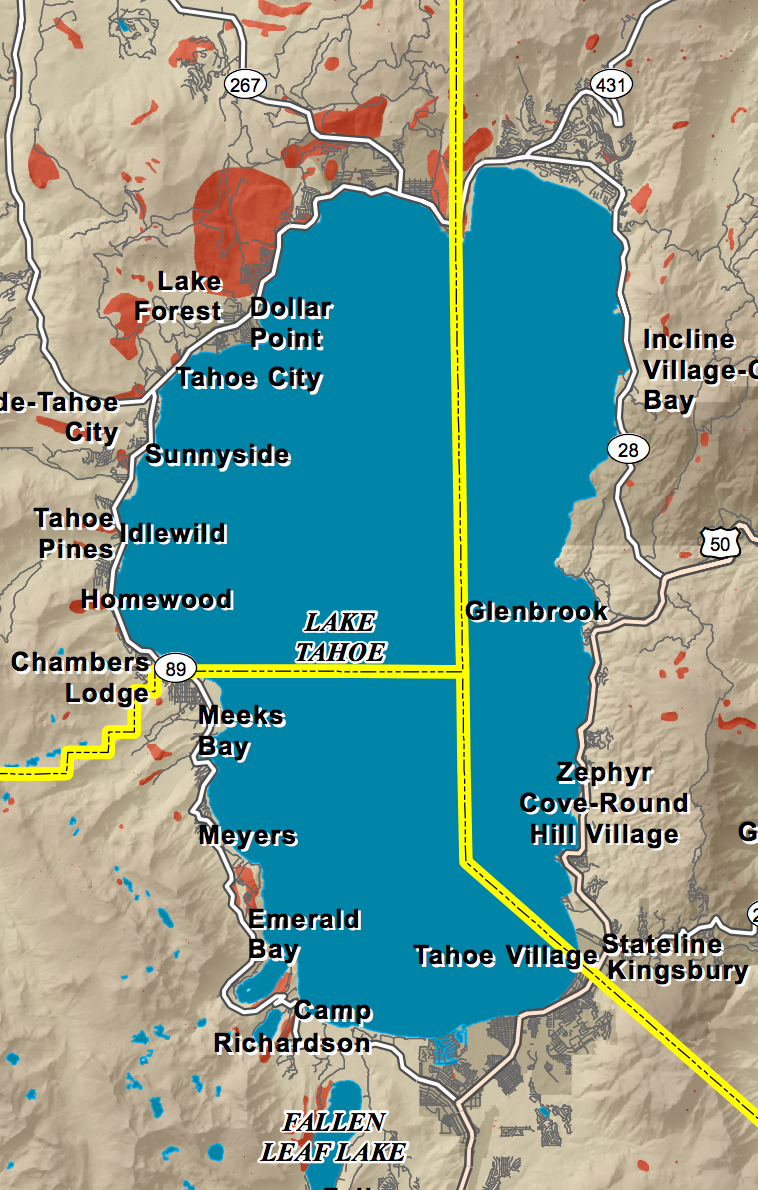

The dark orange represents beetle infestation. Photo/California Tree Mortality Task Force

Mike Vollmer, environmental improvement program manager at TRPA, called the local situation an “epidemic.” And it’s nowhere near as bad as the forests south of here.

“Science says the best insurance we have to stop the beetle attack is to thin out the forests and do the treatments,” Vollmer said.

Local, state and federal agencies have made a concerted effort since the 2002 Gondola Fire in South Lake Tahoe to thin the forests. But it’s a process that takes time and money, and it is work that is only done seasonally. Six thousand acres are under contract this year to be thinned on federal land in the basin, with another 4,000 acres set for next year.

California initially included six counties in its Tree Mortality Task Force. Four were added in June – El Dorado, Placer, Amador and Calaveras counties. The idea is the northern counties will learn from their southern counterparts, with the goal of being proactive instead of reactive.

But it’s not that simple.

“There’s no magic pot of money to address this issue,” Chris Anthony, CalFire division chief, said.

Regulations can impede removal of trees, having no end user for the tree is another issue, and homeowners may not have the resources to fell an infected tree.

Forest Schafer, forester with North Lake Tahoe Fire Protection District, said life and safety need to be the guiding factors when deciding how to go forward. With two-thirds of the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit being in the wildland urban interface and this forest having the highest per acre visitor rate in the national forest system, the urgency is even greater to combat the beetles.

Jeff Marsolais, LTBMU forest supervisor, acknowledged that the regulations in place to get thinning projects approved is slow, which doesn’t work well in an epidemic situation like what is occurring now. Plus, no one knows where the beetles will strike next.

“We don’t actually know the trajectory of the tree mortality for when it will show up on this landscape,” Marsolais said.

Even when the trees are removed there isn’t much market for them.

“There are more dead trees than we know what to do with,” Anthony said.

Board member Larry Sevinson lamented how a biomass plant has been in the works for years between Tahoe City and Truckee, but that now Liberty Energy is pulling back because it’s not financially viable.

There aren’t as many mills. And the infected wood isn’t always desirable. One market for the trees is China, which turns it into coffins and chopsticks. The problem is there is a federal law on the books preventing them from going overseas. This is just more of the regulatory malaise.

What everyone pointed to this time around compared to when there was a bark beetle outbreak in the 1990s is that there is a team in place, people are talking and action is more likely.