No clear winner in decision regarding EDC roads

By Joann Eisenbrandt

A judge has found portions of El Dorado County’s Measure E to be valid, while striking down others as unconstitutional.

Measure E is the controversial voter-approved roads and land use ballot initiative from June 2016.

The initiative passed by a slim margin last summer following a contentious fight over whether it would really do what it said it would—prevent gridlock on county roadways and keep El Dorado County rural.

The rationale behind Measure E

Measure E’s goal was to reinstate the original intent of Measure Y, the so-called Control Traffic Congestion Initiative passed in 1998 by voters. Measure Y was to be in effect for 10 years. In 2008, it was approved again by voters along with the county’s 2004 General Plan, but with some modifications.

Measure E proponent Sue Taylor believed those changes weakened key provisions related to the traffic impacts of new residential development.

She told Lake Tahoe News, “Measure E was proposed because the Board of Supervisors has not been a good steward of our infrastructure. We felt we had to bring back the stronger language of the original Measure Y.”

Once approved by voters, Measure E’s provisions would become policies in the Traffic and Circulation Element of the county’s General Plan.

Prior to Measure E, the General Plan required developers to pay for all needed road capacity improvements to fully mitigate the direct and cumulative impacts of their projects. The county could do this in two ways. It could either require them to construct road improvements based on the impacts of the project plus 10 years of forecasted growth or could put the project and the traffic impact mitigation fees they paid into the county’s 10-year capital improvement plan to fund the construction of project-related road improvements later.

Measure E removed the second alternative, calling unconstructed highway projects in the CIP “paper roads.” The initiative required that road improvements needed to prevent traffic impacts of a new development from creating level of service (LOS) F on affected roadways be completed before discretionary approval could be given to the project. A discretionary project is one that cannot be built by right, but requires county approvals before it can move forward.

The LOS scale ranks the flow of traffic on roadways from A to F. LOS F is the most congested—essentially highway gridlock.

“Since 1998,” Taylor told Lake Tahoe News, “El Dorado County voters have been saying that they don’t want the traffic created by large residential developments and they don’t want to pay for the measures needed to mitigate that traffic.”

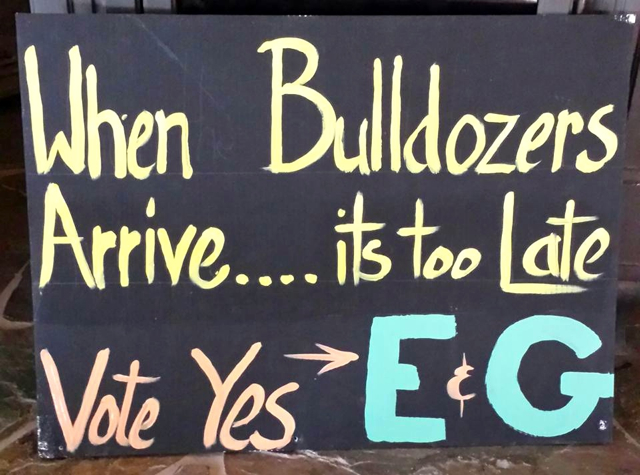

This campaign sign was popular last summer leading up to the election. Photo/Provided

The court challenge

Measure E was to go into effect 10 days after it was declared official on July 19, 2016. On Aug. 28, 2016, the day before this could take place, the Alliance for Responsible Planning, a central player in the pre-election fight against Measure E, filed a lawsuit in El Dorado County Superior Court. Their brief alleged Measure E was unconstitutional because it required project developers to pay more than their “fair share” of the costs to mitigate roadway impacts associated with their specific projects. It also said the initiative was internally inconsistent and not in conformity with the county’s 2004 General Plan.

Last month, almost a year after the filing of the lawsuit, El Dorado County Superior Court Judge Curt Stracener handed down his 49-page final ruling. It struck down as unconstitutional Measure E’s changes to Policies TC-Xa3 and TC-Xf in the General Plan that obligated developers to construct all road improvements prior to project approval. The judge said, “This would require property owners/developers to pay for not only the project’s incremental impact to traffic congestion of the county road system, but also be responsible to pay for improvements that arise from the cumulative effect of other projects, and in some instances to pay for projected future increases in traffic. This clearly exceeds the developer’s fair share in that it is not roughly proportional to the project’s traffic impact it seeks to address. “

The Alliance’s response

The Alliance posted a response to the judge’s decision on its website. “The ‘no growth’ proponents of Measure E promised voters that the initiative would make an affected development project pay for the full cost of improvements to regional roads and Highway 50 … Proponents could not deliver on these promises, however, because the power of the initiative does not authorize voters to enact laws that are unconstitutional or violate state law.”

James Brunello, attorney for the Alliance in the lawsuit, told Lake Tahoe News, “We believe the judge did a great job. His logic was good in crafting the judgment. We are not concerned with the parts of Measure E that he kept. There are no plans to appeal his decision at this time.”

Brunello went on to say, “There is a difference between Measure E and Measure Y. We totally support Measure Y. When it was adopted, the engine that drove it was that new developments pay 100 percent to mitigate all their (traffic) impacts. The mechanism was compliance with the Mitigation Fee Act and everybody paid their fair share. Measure E threw a monkey wrench into Measure Y and changed the will of the voters.”

Measure E proponents disagree

The Alliance’s lawsuit was against El Dorado County. Taylor and Save Our County joined the lawsuit as respondents/defendants and intervenors as Measure E’s proponents. Their brief to the court pointed out their key contention. “… for a project that will worsen traffic on a road facility that is cumulatively projected to exceed LOS standards, the necessary improvements must be constructed, as payment of TIM fees coupled with reliance on the CIP project will not suffice.”

Taylor said of Stracener’s ruling. “The intent of Measure E was not to have paper roads. He took the essence of the measure out.” She likened road capacity to filling up a bucket. “Once you’re reached the maximum capacity of a bucket, you have to say, ‘No more.’ Putting money in the capital improvement plan is not reality. Once you’ve filled up the bucket, just because you have a road on paper doesn’t mean there is any way to put it into the bucket.”

Other Measure E components affected

Measure Y originally prohibited the county from adding roads to its existing General Plan list of highways allowed to operate at LOS F without first getting voters’ approval. The 2008 version of Measure Y allowed the board to add roads to that list without voter approval by a four-fifths vote of the supervisors. Measure E took away this power from the board. Stracener upheld that change.

Measure E also reinstated Measure Y’s 1998 prohibition of the use of county tax revenues to fund road projects that serve new development. The court ruling struck down this change as well as Measure E’s requirement that mitigation fees and assessments collected for infrastructure must be applied to the geographic zone from which they originated.

Opponents of Measure E had said it would negatively affect the county’s ability to meet state-mandated affordable housing requirements and conflicted with General Plan policies aimed at meeting them. California law requires that each jurisdiction’s Housing Element includes enough available land to meet regional housing needs at all income levels. The court found that Measure E’s policy that traffic from residential projects of five or more units shall not, “result in or worsen, Level of Service F” did not “impede or frustrate” these goals. His ruling allowed this policy to stand.

Defining the board’s role

Once an initiative is passed by voters, it becomes the role of the jurisdiction’s governing body to adopt and then implement it. The courts have said the board’s responsibility is to determine what the voters’ intent was when they approved the initiative and to carry out that intent. As County Counsel Michael Ciccozzi told the board at its Aug. 30, 2016, meeting, “You don’t substitute your policy judgment for that of the voters.”

Stracener spoke to this mandate in his ruling. He referenced a number of decisions by the courts in other lawsuits regarding how a voter-approved initiative should be construed. Wherever possible, courts must construe an initiative measure to ensure its validity and assume its proponents understood the constitutional limits on its power. However, initiatives are also subject to the same constitutional limitations and rules as other statutes are. Determining what the voters intended in approving the initiative is essential. The courts look first at the language of the initiative itself. If this is not ambiguous, then that is taken as the intended meaning. If the language is ambiguous, then the courts consider ballot summaries and arguments to determine the voters’ intent.

The board chooses a path

At its Aug. 30, 2016, meeting, the board decided to move forward with deciding how it should interpret and implement the initiative even as the challenge to Measure E in the courts continued to play out.

County planning staff presented a resolution for the board’s approval based on a lengthy, detailed staff memo. The memo contained section-by-section recommendations on how staff felt Measure E could be successfully interpreted and implemented. Taylor and Save Our County believed this was a reasonable solution. As their brief to the court had said, “The diligent work of county staff revealed very plainly that Measure E could be implemented without ‘irreconcilable conflicts’ with the law or the General Plan.”

After prolonged discussion, District 2 Supervisor Shiva Frentzen made a motion to approve the resolution. She told the board, “The voters have spoken. They have voted. If this goes to court are we going to put all the projects on hold? We need to move forward.”

Frentzen’s motion died for lack of a second. District 4 Supervisor Michael Ranalli then moved that the board receive and file staff’s Measure E implementation plan, continue it off calendar and move Measure E forward exactly as written. Ranalli told the board he believed staff’s proposal was more a rewrite of the initiative, not an implementation plan. It would be better, he said, to “let the courts sort it out.” The motion passed with Frentzen dissenting.

Lake Tahoe News made repeated attempts to contact Frentzen, now chair of the board, to get her views on Stracener’s recent decision. She did not respond.

Set up to fail?

Taylor believes the board did not live up to its responsibility to carry out the intent of the voters. “The board appears to be aligned with the petitioners of the lawsuit and they were hoping the entire initiative would be thrown out.” Not making any attempt to interpret or implement it would, she contends, “make it more vulnerable in court.”

Asked by Lake Tahoe News if he felt the county had intentionally left Measure E undefended, Alliance attorney Brunello responded, “We never had a feeling that the county was inviting us to file a lawsuit. The Alliance opposed the initiative itself for a number of reasons, but most important were the constitutional issues.”

The county’s viewpoint

Speaking for the county, paid spokeswoman Carla Hass said in a written statement, “The board made the reasoned decision that it would be best equipped to interpret and apply Measure E when considering its application to a particular project as opposed to speculating how it might apply to hypothetical projects. This litigation was initiated before any project came forward. Supervisor Ranalli also recognized that no matter what the county did, the courts would remain the final arbiter of Measure E because, under our system of government, the judicial branch retains the final check on the constitutionality of any law. Adopting staff recommendations at that time would not have prevented the courts from independently assessing the constitutionality of the measure. “

Asked how well the county has respected the will of the voters, Hass continued, “The county is not in a position to speak to the voters’ expectations regarding Measure E. The county’s role is to interpret and apply its General Plan when considering its application to a specific project.”

The county is in the same position as the Alliance—the court ruling gave neither of them all they had asked for. Lake Tahoe News asked if the county agreed with what parts of Measure E were upheld and which were stricken. Hass replied, “The county recognizes that the initiative power is an important right of the electorate, but any law—even if passed by a majority of the voters—must comply with the requirements of the Constitution and state law. By striking certain provisions down, the county, citizens, and developers have greater clarity about what is required to mitigate impacts.” Asked if the county is considering appealing the decision, Hass stated, “The county has not made a decision at this time.”

Clarity or more confusion?

Taylor does not think the court’s ruling brought clarity. The initiative “now contains parts of the 1998 Measure Y, parts of the 2008 Measure Y and parts of Measure E. I think there is now more confusion than prior to the judge’s decision. The judge just undermined the premise of the voter-approved 2004 (General) Plan and the original intent of Measure Y. I think that was a huge slap in the face to the voters of El Dorado County.”

The road forward

The question remains whether or not Measure E as modified by the court will still achieve its stated goals. Developers of large-scale residential projects that could cause traffic on county roads to worsen and reach LOS F remain required to pay for all infrastructure/roadway improvements their projects create the need for. They just won’t have to pay for and construct them before a project can be approved. The Alliance and the county both believe that the use of TIM fees and the county’s capital improvement plan are sufficient mechanisms to ensure all impacts will be mitigated. As the Alliance’s website statement put it, the judge’s ruling will “restore underlying General Plan policies from voter-approved Measure Y requiring new development to pay traffic mitigation fees to fully mitigate traffic impacts.”

Measure E’s proponents are more cautious. “Measure E was a mandate to the board to consider how projects that create a certain level of traffic impact would mitigate their needed roads,” Taylor explains. “If it was not possible to mitigate, or if the infrastructure was not there to support those projects, then with Measure E the board would be forced to deny those types of projects.”

This mandate is now gone. “The board still has the tools to implement what the voters want even with what’s left (of Measure E). It has now been put at the feet of the board of supervisors. It’s in their hands to do what the people wanted.” Taylor disagrees that Measure E’s proponents are “no growth” as the Alliance has called them. Their goal, she told Lake Tahoe News, is to follow the intention of the 2004 General Plan as outlined on its cover page: “A plan for managed growth and open roads; a plan for quality neighborhoods and traffic relief.”

Stracener’s ruling can be appealed by any of the parties to the lawsuit within 60 days. Measure E’s proponents are still weighing their options and have not yet made any decisions regarding filing an appeal.