Unmasking the many faces of homelessness in Tahoe

By Susan Wood

CAMP RICHARDSON – “It could happen to anyone.” The words of Kasandra, a Tahoe native attending South Tahoe Middle School, resonated with about 120 captivated listeners sitting on both floors of the building.

It was as if the hush over the audience allowed hearing a pin drop at a stunningly quiet Valhalla Grand Hall.

Kasandra has been homeless.

A handful of speakers from Tahoe and Sacramento on Oct. 26 shared amazing stories of resilience, survival and inspiration in overcoming homelessness in their lives. While a Grand Hall blaze burning in the fireplace provided a homey feel, the intimacy and bravery of these people made the Faces of Homelessness a reality to many.

The event was put on by the Tahoe Coalition for the Homeless. It is a nationally recognized program that literally provides a human face to homelessness.

Like other communities, South Lake Tahoe grapples with the issue; having opened a warm room two winters ago. With an overwhelming number of guests considered local, the goal is to get these residents through the harsh winter months.

It’s much more difficult to deem homeless people as “the other” when they’re standing right in front of you. On Thursday night they were pouring their hearts out with the goal of bringing an understanding to the living condition.

With Kasandra, she recalled fondly a time when her family lived in a two-bedroom duplex, until life’s unpredictable circumstances took over. Something changed “all in one night.” A big fight between her parents sent her father to jail. He was the breadwinner and couldn’t remain so when he got out.

With a straight face, the young girl remembered her family moving in and out of different living arrangements – staying at Campground by the Lake, walking around and napping in the Stateline casinos and at her mother’s friend’s place.

Surprisingly, but in the true nature of a Tahoe kid, Kasandra didn’t mind some nights outdoors because “I love the wilderness.” She got a few smiles with that declaration.

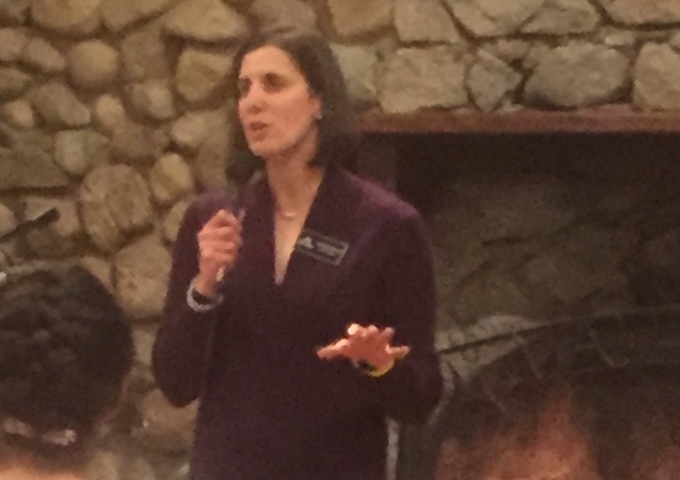

Marissa Muscat on Oct. 26 talks about homelessness on the South Shore. Photo/Susan Wood

She’s not alone

Another youth opened her story with a rhetorical question about: “What is normal?”

Erin Cox might have related to some degree with Kasandra’s outdoor experience – except that living indoors felt like staying outside.

Given that Lake Tahoe’s elevation is situated at more than 6,000 feet, the South Tahoe High School senior remembered being so cold living in a shed with no insulation or plumbing that she experienced a panic attack.

Her mother, who endured a debilitating illness since the girl was 5, “was violently ill.” The circumstances kept the family in an unfortunate web of poverty. Even though Erin ended up in Child Protective Services and has ultimately found an outlet in playing volleyball, she knew her mother loved her.

Seeking a father’s love

This was more than Wesley Colter of Sacramento could say about his upbringing. All he ever wanted was acceptance from his raging, alcoholic father.

What appeared to be a “normal” childhood from the outside – full of material goods and the nice house – turned out to be anything but. His father made it known that his son got in the way.

He characterized his interaction with his father as “neglect” when he did something right and “attention” when he did something wrong.

And then there were the times as a child when life was totally out of his control. Once when left alone by his father, he was sexually assaulted – a secret he kept for 25 years.

“It changed me forever,” Colter said.

The trauma set into motion a downward spiral that sent Colter living in the streets as a teenager, fighting, stealing vehicles and taking drugs. He consequently got involved with the wrong crowd.

“The minute they placed a meth pipe to my mouth, I immediately felt a part of,” he said. “Addiction ruled my life.”

The tribal experience sent him to prison at age 19. He was thrown behind bars as an “unsuccessful transition” nine times.

He finally turned his life around when he sought counseling, assistance from community resources, faith and a sober lifestyle.

Since he spent most of his life wanting to relate to others, it was only natural he would find a new lease on life helping others make the journey out of despair as he did.

Colter became a drug and alcohol counselor – the brightening light at the end of tunnel.

The darkness of the past

David Husid, today a vice president with Cottage Housing in Sacramento, knows all about the destruction of substance abuse.

His journey from his middle class life started with him feeling “special” because he was adopted. That was until he turned to drugs and alcohol later in life. He enjoyed the social aspect of it, but deep down sensed it could ruin his life. He left the San Francisco Bay Area – blaming the region for his condition. He moved to Sacramento. His problem only followed him. Husid hid the addiction from his wife, whom he cheated on in a drunken stupor.

With a “one-strike, you’re out” mentality, she threw him out of the house and onto the street.

“What happened to my life?” he asked himself, while preparing to leave the house. The question turned out to be prophetic to what came before him.

Husid was running a high-dollar money-laundering scheme and substance abuse fed a manic need to be successful. But crime only pays for so long.

He was sentenced to six years in Folsom State Prison, where it took his hardened cellmate to wake him up.

“Dave, what have you done with your dash?” the cellmate asked, referring to the symbol on a tombstone. It was the man’s way of saying that he was wasting “a once promising life.”

Husid, now with degrees and drug and alcohol counseling certifications, was crying.

Feeling a connection

Many tears flowed, and some attendees shook their heads at what they were hearing. Many stared in disbelief at how stacked the odds were against those sharing – sometimes illustrating a consistent pattern among the adults identified as homeless at one point in their lives.

Homelessness can be a symptom to a greater pain – not the root cause of troubles.

The hosts and brainchildren of the evening – physician Marissa Muscat and rabbi Evon Yakar – were visibly moved by the connection between each homeless survivor and community members.

In the middle of the sharing, Yakar circled the large room to ask what one word comes to mind in hearing the stories. The responses ranged from “brave” and “desperation” to “family” and “support.”

Muscat, the local coalition’s executive director, choked up while she shared about a homeless hospital patient at Barton.

“Jorge” had asked himself at the peak of his troubling life: “How did I get here?” He was laid off from work and through challenges ended up on the street. She recalled their three-hour conversation at the end of his bed.

Today, he has turned his life around. His story inspired Muscat into action that resulted in her work for the coalition.

“I’m so proud to be part of this community,” she said.

Under Muscat’s directive, the Tahoe coalition is seeking space for a facility to house up to 25 individuals. At least 2,000 square feet is required, in which case, the coalition will pay $1- to $2 per square feet in rent depending on size and utilities. Interested parties may contact Muscat at tahoewarmroom@gmail.com.

Last year’s warm room on the South Shore, which operated December through April, served an average of 27 guests nightly. The bulk of them were aged between 31 and 50. With 108 coming in, men more than doubled the number of women. Seven families with children younger than 18 were provided motel rooms.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development reported that on a single night in January 2015 California’s homeless numbered 115,738. That figure accounted for 21 percent of the nation’s homeless population.